Reflections on Writing Autocrats vs. Democrats

On the challenge of weaving history, ideas, and policy into one story

Autocrats Vs. Democrats is a book that aspires to synthesize a wealth of history, academic literature, and policy prescriptions into one volume. It’s the most ambitious book I’ve ever written. That may also explain why it was many years in the making

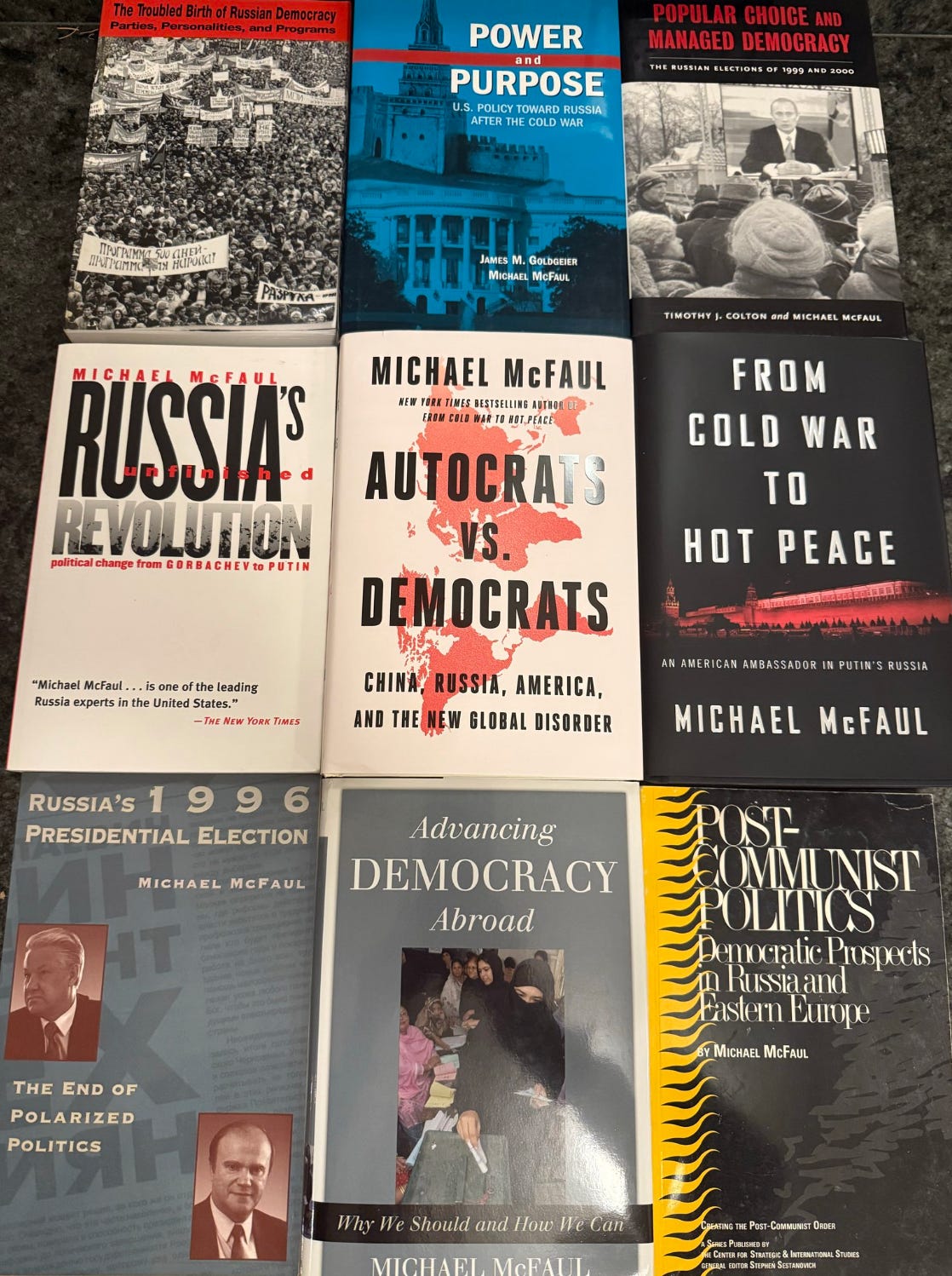

In my previous books (you can find all of them here), I had somewhat different goals. Some books are based on original research about a very specific period in history. For instance, to write Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin, I cited many original documents, often in Russian, and conducted hundreds of interviews with key players in Russia to document the process of regime change in the Soviet Union and Russia from 1985-2000. Writing with Jim Goldgeier, Power and Purpose had a similar goal and research method in tracing U.S.-Russia relations over two decades.

In some books, I delved deeply into explaining a single election, such as the one I wrote with Tim Colton on the 1999 parliamentary and 2000 presidential elections in Russia that brought Putin to power. For that book, we also generated original data by doing public opinion polling in Russia. A book I wrote about the 1996 presidential election in Russia had a similar strategy—tons of details about that electoral year.

In other books and articles, I proposed a sweeping hypothesis that I then tried to support with data. My book, Advancing Democracy Abroad, is in this genre. I argue why democracy promotion serves American national interests and then marshal evidence to support that claim from a wide range of sources. I have written many articles using a similar research strategy, drawing on the work of others—for instance, those who study the relationship between democracy and development—to support my hypothesis. That book also ended with some policy recommendations.

My last book, From Cold War to Hot Peace, had a unique research design for me. In one book, I tried to explain the rise and fall of cooperation in U.S.-Soviet and U.S.-Russian relations by synthesizing a lot of academic literature, including my own, without excessively referring to political science theories. Instead, these theories served as a hidden architecture for the book that academics would quickly recognize, but hopefully non-academics could digest without being burdened with all the jargon of political science. Then, on top of the big policy-driven argument, I shared my personal story, from being a student in the Soviet Union to serving as the U.S ambassador in Russia. This was the first book in which I have used the word “I.” That was hard. It was also depressing because the story is essentially a tragic one. I had high hopes for Russian democracy and U.S.-Russia cooperation that eventually were not realized. But that method—part history, part political science, and part memoir—was also rewarding, as I got to tell some stories. Stories about dancing the two-step in Moscow or using Twitter as a U.S. ambassador are typically not allowed in either academic books or journal articles.

Autocrats vs. Democrats has some level of original research as well as a few vignettes from my personal story. But more so than any other book I’ve written, Autocrats vs. Democrats attempted to synthesize a vast amount of historical and social science literature and provide policy recommendations for the United States based on this analysis.

The first part of the book is explanatory. To explain our current era of great power competition, I wanted to see if there was variation in the past. In research design, variation in the dependent variable is always preferred. There was, but to be able to measure the changes in the factors (in the language of political science, the “independent variables”) that drove cooperation and conflict, I had to go way back in history. The book starts in the 18th century! You need that much time to see changes in the “power” variable. You also need a lot of time to see changes in the “regime” variable. But I knew that my readers (and my editor!) would not want to plow through hundreds of pages of history before getting to the main part of the book. So, I had to synthesize 250 years of U.S.-Russia history into 30 pages. The same is true for U.S.-China relations. That was hard. It meant I had to simplify a lot, exposing me to critiques from actual historians of this diplomatic history. But I hope that most readers will only want to read 30 pages on this history!

The second part of the book summarizes a ton of data measuring the current balance of power, the contours of ideological competition, and the differing conceptions of the global order among China, Russia, and America (the order of these three countries is based on the alphabetical order of their official names: the People’s Republic of China, the Russian Federation, and the United States of America). To do in just nine chapters again required significant simplification and hard choices about what to add and what to cut. Remember, the first draft of the book was 1,200 pages and had over 5,000 footnotes.

This section of the book also required me to make some very hard assessments about future trajectories of power, especially regarding China. I want to admit right now that I am uncertain about my final assessment. In addition, in this section of the book, I had to make educated guesses about the intentions of leaders in the United States, Russia, and China. I feel pretty confident about my assessments of Putin’s thinking. Because I do not read Mandarin, I feel much less confident about my assessment of Xi’s thinking. Thankfully, we have an army of fantastic experts on China who write in English and who I relied on heavily for this part of the book. During the second Trump administration, I often feel like I’m working with incomplete information, since the current U.S. president frequently changes his positions — or, put more diplomatically, he demonstrates considerable flexibility in his foreign policy goals and strategies. For instance, in the first Trump administration, many senior foreign policy officials in his government assessed the China threat more gravely than Trump seems to do so today. Conversely, Trump, in his first term and in the first months of his second term, spoke fondly about his friend, Putin. Yet, lately, after the book had already gone to the press, he has been more critical. Writing about contemporary international politics is hard! Things are changing so fast.

The third part of the book is prescriptive. For two of these chapters, I draw on lessons from the Cold War—both mistakes and successes—to make policy recommendations for dealing with China and Russia. The third chapter in this section discusses issues in great power politics, particularly in U.S.-China relations, that have no parallels in the last century. When writing about the Cold War, I returned to familiar ground. I wrote my PhD (or DPhil, to be precise) at Oxford University about great power competition in southern Africa during the Cold War. It was good to revisit this history. But again, the task of synthesis was enormous. I wanted to convey lessons from the Cold War without retelling the entire history of the Cold War.

When asked, “Who is the audience for this book?” I have constantly answered that it is all Americans first, and citizens of the world second. I refused to oversimplify too much to make it a “pop” book, but also deliberately kept out academic and policy jargon to make it accessible to all. Experts on Russia, China, or U.S. foreign policy might not learn much from the sections of the book on which they are experts. But by synthesizing the big literature on all three topics, I hope that all readers will learn something! In writing Autocrats vs Democrats, I most certainly learned a lot! My main goal in trying to synthesize so much, however, is to spark a serious debate about America’s future in the world—one that takes place not only in Washington, DC and Palo Alto, California, but also in Bozeman, Montana, San Antonio, Texas, Boise, Idaho, and elsewhere.

In 1978, journalist and historian of science James Burke presented a groundbreaking series on the history of science and technology titled “Connections.” In a television series spanning ten episodes - and a companion book that he wrote for the Series - Burke explained how technological change is far from the straight line that most of us believe it is, that in reality technology changes unevenly, randomly, indeterminately, and contingently.

But it is in his final episode (“Yesterday, Tomorrow, and You”) that Burke lays out many of his most powerful - and prescient - viewpoints.

In one segment of the episode, Burke discusses the trade-offs that come from developing highly specialized knowledge that allows experts to become more precise, but, at the same time, becomes more and more difficult for the person on the street to understand.

“In the absence of knowledge,” Burke tells his audience, “what we are left with is emotion.”

And then, Burke continues:

“But what happens when I do care, when say the people we vote for are making decisions that affect our lives deeply, ‘cause that is after all when we get our say, isn’t it, when we vote?”

That is why your book matters, Professor McFaul.

That gap between “experts” and the “person on the street” must be bridged. And so must the Past, Present, and Future.

Our survival depends on it.

Aloha 📚🤙🏼

Prof. McFaul, maybe it’s because of your innate sense of diplomacy, but I think you give too much credit to DT. He doesn’t plan anything—unless it’s an illegal plan to extort or confiscate money for himself. He’s oblivious to

everything else.