The Limits of Coercive Power

If we continue to bully and berate our allies and partners, they will eventually find other friends

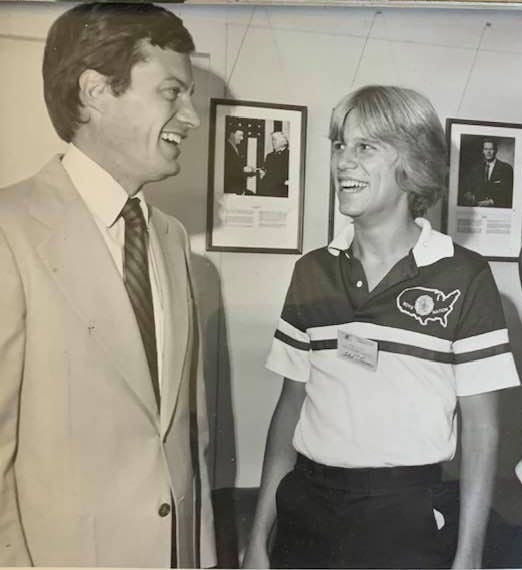

As a kid, I lived in three different cities in Montana but spent most of my time in Butte (from 3rd to 10th grade). Back then, Butte was a rough mining town—lots of bullies, gangsters, and fighting. I got into fights, too—or more accurately, I got beaten up—and even was once suspended in 9th grade for defending myself when a bully ambushed me one night on the premises of West Junior High (You could fight elsewhere, but not on the school grounds). The gang that terrified us the most we called “Eddie and the ***.” (I’m censoring what we called his gang.) Eddie and his sidekicks terrorized our neighborhood, coercing kids to do all kinds of things they didn’t want to do. The “balance of power” between these guys and my friends was asymmetric; when we saw “Eddie and his thugs, we ran. If they cornered me, and they did at times, I would come bloodied. One afternoon, they even chased me into my own house. My mom used a broom to chase them away.

Eddie had a lot of what international relations scholars call “coercive power” over me and others. When dealing with weaker kids like me, he usually got his way. But no one respected Eddie and his gang. No one thought that Eddie was “Great”!

I was reminded of Eddie as I watched President Trump wield coercive power in his foreign policy over the last two weeks. Because there is no higher authority in the international system, power is what matters most in relations between countries, though it is not the only factor. Harvard professor Joseph Nye defines power as “the ability to affect others to get the outcomes one wants.” (See Nye’s book, Understanding International Conflicts, p. 61.). States, like individuals, can deploy power in different ways along a continuum of coercive power versus cooperative power. Coercive power is what Eddie used all the time; he compelled people like me to do what we did not want to do because he could inflict pain otherwise. Coercive power usually produces zero-sum outcomes—the powerful get more, and the weak get less. Cooperative power is different. Cooperative power produces win-win outcomes. Like market transactions in which the buyer and seller both benefit from the exchange, everyone is better off from international cooperation, both the weak and the strong.

So far, in his second term, Trump has leaned into using coercive power, and he’s achieved some wins. He deployed coercive power successfully against the government of Colombia, compelling it to capitulate to his demand of letting the U.S. military planes land there. Last weekend, Trump deployed another tool of coercive diplomacy—tariffs—against Canada, Mexico, and China. It looks like this attempt has been successful, too, specifically in getting Mexico to deploy 10,000 troops on the border (although some reporting suggests that there were already roughly 15,000 soldiers there, meaning Trump’s coercion achieved no change in Mexico’s behavior.) Trump has also threatened to use coercive power to take control of the Panama Canal and Greenland, even though the citizens of Panama and Greenland are not interested in such transactions. They are being coerced, not persuaded.

Some commentators have celebrated this return of “gunboat diplomacy.” American swagger is back, and good things will happen, so they trumpet. I have my doubts, especially over the long term.

To be sure, all great countries use coercive power from time to time. (Alex George, my advisor during my undergraduate years at Stanford, was one of the world’s leading experts on coercive diplomacy. Check out his book, The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy.) Sometimes, they even deploy military power, the ultimate coercive instrument. And over the centuries, many empires enriched themselves through coercion, including war, annexation, occupation, and colonization. In earlier eras, conquest was profitable. (See Peter Liberman’s book, Does Conquest Pay: The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies?) But more recently, say, in the last hundred years, coercion has proven less effective, better at producing short-term gains at the expense of long-term positive objectives. Most empires have collapsed. The imperial expansion has ended. Occupation is costly (as we learned in Afghanistan and Russia is learning in eastern Ukraine.) Coercive power is especially difficult to sustain over time when more than one great power dominates the international system. When there is only one hegemon, weaker powers have no choice but to acquiesce to the whims of the coercive superpower. However, systems with two or more superpowers give weaker states options.

And that’s precisely what we have today—an international system with at least two great powers—the United States and China. Weak states that do not like being bullied by Trump States can turn to Xi’s People’s Republic of China. To be sure, China deploys coercive power, too. Ask the Taiwanese, South Koreans, Australians, or Lithuanians. But Xi and his Communist Party have also developed an array of foreign policy tools designed to achieve win-win outcomes with their partners, including, most notably, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), but also the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and BRICS together with its affiliated National Development Bank. While Trump threatens countries to produce zero-sum outcomes, Xi offers aid, trade, and investment opportunities to achieve win-win outcomes. You do not need a PhD in international relations to predict which one of these strategies will endure over time. Even American allies will gradually become more cooperative with autocratic China if all we do is bully and berate them.

That said, it’s only been two weeks. It’s not too late for Trump and his team to rethink their singular focus on coercive foreign policy tactics. In addition, the United States is not a monarchy or a country run by gangsters like Eddie. Hopefully, our democratic institutions and norms will allow the American people to engage in a substantive discussion on the wisdom of only relying on coercive power for our security and prosperity.

By the way, different from Eddie, I took a more cooperative approach to my “bilateral relations,” cultivating “win-win” ties with friends, teachers, and mentors, which landed me on an educational and career path I love. I heard second-hand, but cannot verify, that Eddie eventually ended up in prison.

The art of diplomacy is to get another nation to do what you want them to do. Madeline Albright

Diplomacy isn't just about friendly conversations and agreements, but also about advancing a nation's interests and achieving its objectives on the international stage. This can involve negotiation, persuasion, compromise, and sometimes even applying pressure to influence other countries' decisions and actions.

What "other friends" are there to be had? The main antagonists that you might be alluding to are all facing some form of their own existential threats - most of which are internal and self-inflicted. None of them really are in a position to offer anything of durable value to our current allies and partners. Russia is bankrupt; China's Belt and Road has been called out globally for what it really is and their economy is levered 3x as much as our own; Iran and North Korea are tittering on the verge of complete regime collapse.

With the exception of the UK, the major states of the EU are tacking towards their own forms of nationalism slightly out of sync timeframe-wise from the US. The current ruling party in the US (I dare not call them Republicans because they don't resemble anything like the party I'm familiar with) will reliably overplay and misread its "mandate" as so many administrations - of both political persuasions - have done over our modern history. We're already seeing it happen in real time.

Count on midterms to reset the political landscape, as they almost always do. And should the Democrats be able to stop their seemingly endless tendancy toward political self-immolation, their re-ascendency is just about guaranteed.

So, our allies and friends are likely just going to wait us out. A political form of shadow-boxing, if you like.