Through Engagement, Americans Must Keep Learning about China and the Chinese Must Keep Learning about America

We can do both – stop spies and welcome scholars and students – at the same time.

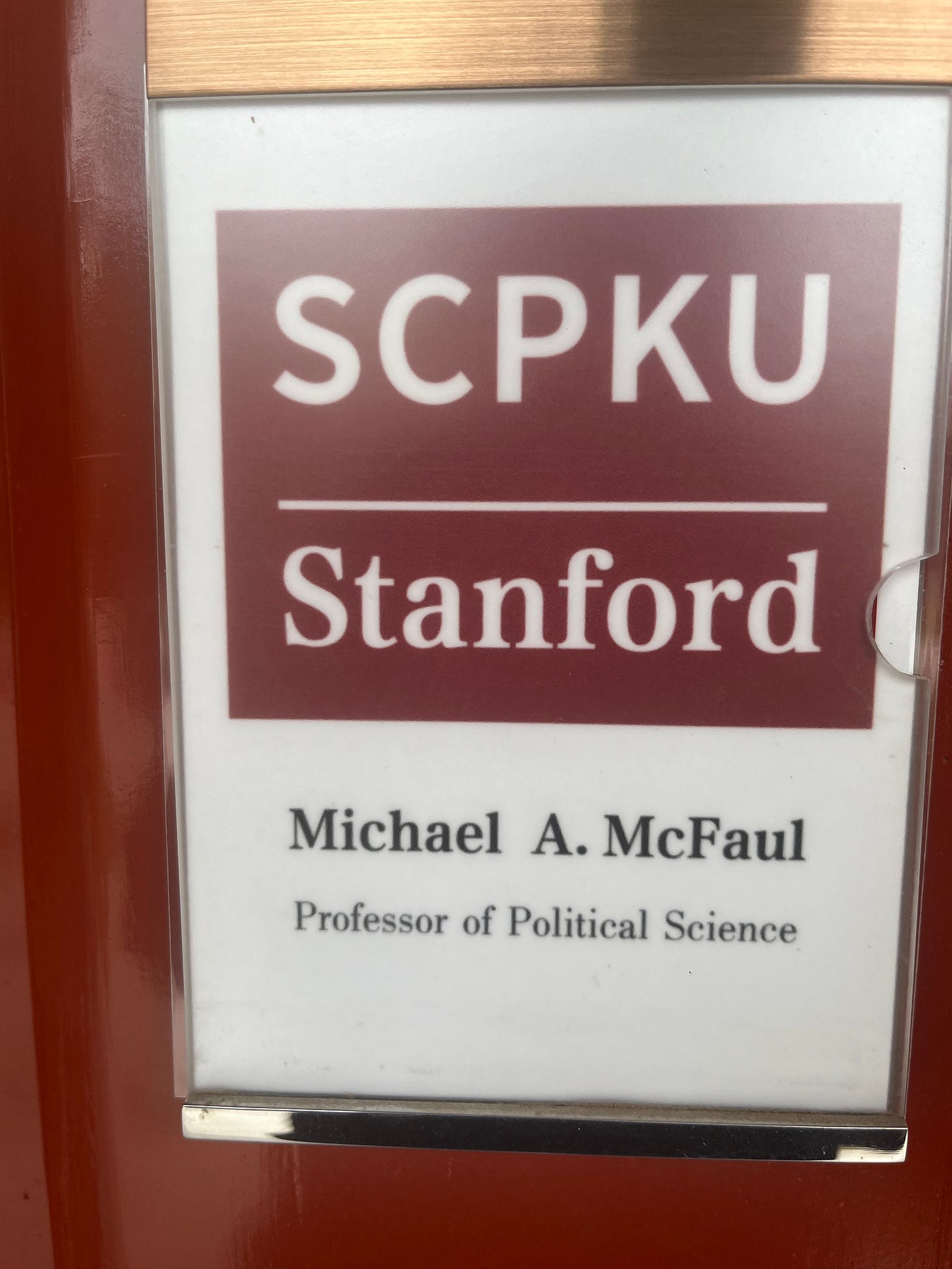

This month, I spent two weeks in China. Because of COVID-19, it was my first visit since 2019. I was there for two reasons: (1) I taught a mini-course on U.S.-China relations at the Stanford Center at Peking University (SCPKU) to students from both Stanford and Peking and (2) did a bit of research for my forthcoming book: Autocrats Versus Democrats: Lessons from the Cold War for How to Deal with China and Russia Today. Check out my syllabus here as well as this piece to get a flavor of some of the arguments I make in my book. Though I had limited time for my own research, I did have a chance to meet with scholars from think tanks (including some tied to the Chinese government) and professors and students and at Peking University, Tsinghua University, Beijing Normal University, the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, and the Renmin University. I also met with two ambassadors to China, U.S. Ambassador Nicholas Burns and Ukraine’s Ambassador Pavlo Riabikin, business people, and a small number of officials from the government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

A few years ago, there would have been nothing special about such a trip. In fact, I spent chunks of my 2015 and 2019 summers at SCPKU doing research for my book. (Yes, this book is taking me too long to write! The world keeps changing!) But 2024 is a different era in U.S.-China relations. Since my last visit, many analysts have suggested that we have now entered a new Cold War with China. In 2019, the historian Niall Ferguson wrote, “When did Cold War II begin? Future historians will say it was in 2019.” China expert Susan Shirk opened her 2023 book Outreach with the blunt statement, “A new Cold War has already begun.” New York Times reporter David Sanger’s 2024 book is called New Cold Wars: China’s Rise, Russia’s Invasion and America’s Struggle to Defend the West.

In this new era of confrontation between the United States and China, many American scholars no longer travel to China. Some feel unsafe and, rightfully so, worried that China’s new security laws will make their questions of research illegal. Several American student programs in China have been canceled or remain dormant. The U.S. Fulbright Scholars Program to China has been suspended. In fact, this was the first time that Stanford sent students to the PRC in several years.

I want to admit candidly that I was nervous about going too. I first wondered if I would get a visa. After all, I am an unapologetic promoter of democracy and human rights, have written many critical things about Xi, and served on the board of the National Democratic Institute, which the PRC has sanctioned. I am already banned from traveling to Russia and Iran. I worried that China would follow suit. Second, I worried about endangering people whom I met. Third, I was concerned, albeit only slightly, about being detained. Remember, in 2018, the Chinese government egregiously violated international law by detailing two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, on false espionage claims, in retaliation for the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver. (Meng had been detained in Vancouver at the request of the U.S. for allegedly circumventing trade sanctions with Iran.) In 2021, Beijing released the two Michaels, but only after Canada allowed Meng Wanzhou to return to China instead of extraditing her to the United States. Americans have been arrested and detained too. Though I knew that the probability of my arrest was low, such horrific abuse of autocratic power against foreign nationals scared me. I know it has many other Americans convinced not to travel to China anymore. I also worried about the ethical issues of traveling to a country committing gross human rights violations, especially in Xinjiang. In the late 1980s, as a PhD student studying national liberation movements in southern Africa, I respected the academic boycott against doing research in South Africa. Wasn’t traveling to China to do research hypocritical? And of course, I worried about all the surveillance issues.

In the end, though, I decided the benefits of traveling to China outweighed the downsides. In future essays, I will share my more substantive takeaways from my trip on topics such as the bilateral competition in AI and electric vehicles, the growing influence of CCP in academia, and arms control. But in this essay, I want to focus just on one issue: the benefits of talking and engaging with the Chinese via both government and societal channels.

In my many meetings with Chinese scholars, officials, and students, I was struck by how little they knew about basic dynamics in American politics and foreign policy. The reason was obvious: they had not met with Americans in some time, be it with professors like me or students like our group from Stanford. They were isolated. Obviously, Chinese censorship doesn’t help. But COVID-19 and new fears and restrictions about travel also have contributed to the dramatic reduction in engagement between our two societies since my last visit in 2019. I also was struck by some of my misconceptions about China after a five-year absence. Even little things, like the fact that China is now a completely cashless economy – no paper money and very few credit cards – make a bigger impression on you when you witness them firsthand rather than read about them from far away.

As the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, I always explained to my team that were going to have fundamental disagreements with Putin and his entourage and that hundreds of hours of talking would never resolve some issues. Tragically, this became even more true after I left Moscow in 2014. But we should never allow disputes of conflict based on misperceptions and bad information. Engagement and interaction help to reduce misperceptions. Even those most hard-core China hawks (a term I actually don’t like) should want, as Sun Tzu allegedly advised, to “know thy enemy.” We will know China better if our government officials, scholars, and students travel there. I welcome Secretary Blinken’s current visit to China. If nothing else, he will gather some intelligence on CCP’s intentions and reasoning. That’s better than just reading CIA reports on these topics.

If we are going to be competing with China for decades, we need to invest more in understanding China. We need more professors who really understand that place to teach our future leaders. We need more students to learn Mandarin and then spend time in the PRC. During the last Cold War, I was a student at Leningrad State University in 1983, the Pushkin Institute in Moscow in 1985, and the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland in the summers of 1985 and 1986. Those were transformative experiences that helped me understand the nature of communism. We now need experts on China, and traveling to and studying in China must be part of that training. Today, many of my students at Stanford fear that if they were to spend any time in China, they would not get a security clearance to work in the U.S. government later. That needs to change. As a first step, officials in charge of issuing security clearances should coach students going to China on what they should and should not do while in China to be able to get a security clearance upon their return.

We also should make it easier for Chinese specialists studying the United States to travel to the United States to do fieldwork. I heard horror stories of scholars being denied visas or interrogated for hours at arrival. That’s no good. We want Xi and his advisors to understand us. We want American Studies to grow in China. We should be sending more of our specialists to China to teach courses there. As the first step, the Fulbright program for China must be resurrected. We also want Chinese students to continue to study at American universities and not just STEM, but the social sciences and humanities. And if Chinese students major in the social sciences or humanities, we should allow them to spend three years working in the United States as we do for STEM majors. The more they know about the United States, the better. Of course, we need vigilance regarding Chinese spies. But we can do both – stop spies and welcome scholars – at the same time.

In my course, I had a handful of students from Peking University. I did not change a word on my syllabus from the last time I taught this course this past Winter Quarter. I purposefully set up debates on topics such as “China is an ideology power” or “The United States is a declining power.” In one session, a student from Peking University had to argue that “the United States should promote democracy abroad.” An American student had to argue that “the United States should not promote democracy abroad.” There were some heated discussions. But it worked. I think our Stanford students learned a lot from having Peking University students in the seminar. I hope the same for our Peking University colleagues. In fact, one of them told me that it was a transformational experience to be compelled to wrestle with alternative hypotheses on sensitive issues and then have to discuss them in class (and not just listen to a lecture.) These kinds of small breakthroughs are good for the advancement of knowledge. Engagement for the sake of understanding is better than isolation.

After the authorities review my syllabus and my meetings, I hope I will still get another visa because I am still not done with the book! I’ll let you know.

Brilliantly designed syllabus; the final student papers, beyond the live debates, will be enlightening. As a journalist and business communicator who lived in Hong Kong (Richard Boucher became a frequent acquaintance), criss-crossing China many times over 14 years, and handling Jiang Zemin's visit to Boeing in 1993, I wholeheartedly concur there's more to gain from dialogue and discussion than confrontation. Young American scholars should study China's social sciences and humanities as they should ours -- with the cautions you cited. I believe, well knowing of what Xi Jinping is doing ideologically and militarily, that China doesn't want to come out on top as much as alongside. I hope I'm right and that Secretary Blinken's trip, now underway, is as fruitful as your well-timed visit.

Thank you for this report and looking forward to the next ones on China. These international student programs are indeed transformative. Not only do they enlighten students about their host countries but they shape students' thinking about their *own* countries and foreign policies as seen from abroad.